In a journal entry dated July 17, 1956, Thomas Merton included a section he named, “Prayer to Our Lady of Mount Carmel.” He was remembering an experience that he had some 16 years earlier during a visit to Havana, Cuba. A younger TM writes about this experience in another journal entry, this one written in New York on May 21, 1940:

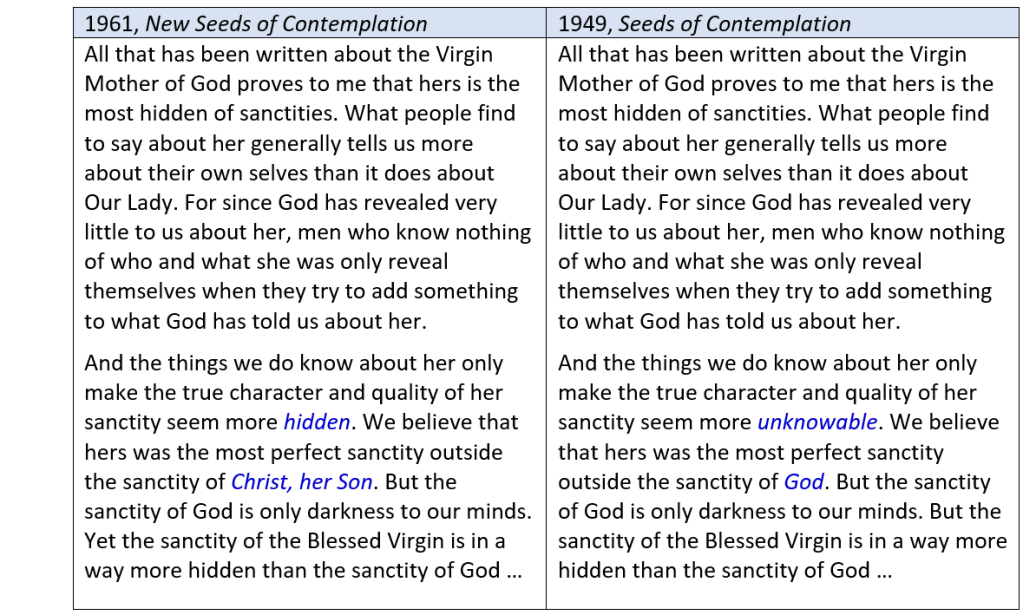

The room I had in Havana, in a cheap hotel up by the University, had a hard bed which frequently collapsed. It was on a corner of the building and one window opened towards the fake Columbia of the university, the other towards the Calle San Lazaro. Through the other came the reflection of a tower of Nuestra Senora del Carmen, and the great statute of the Blessed Virgin was caught in the mirror of my wardrobe, and I could look at it when I woke up in the bed, reflected there, with the sky behind it unusually white in the glass. 1

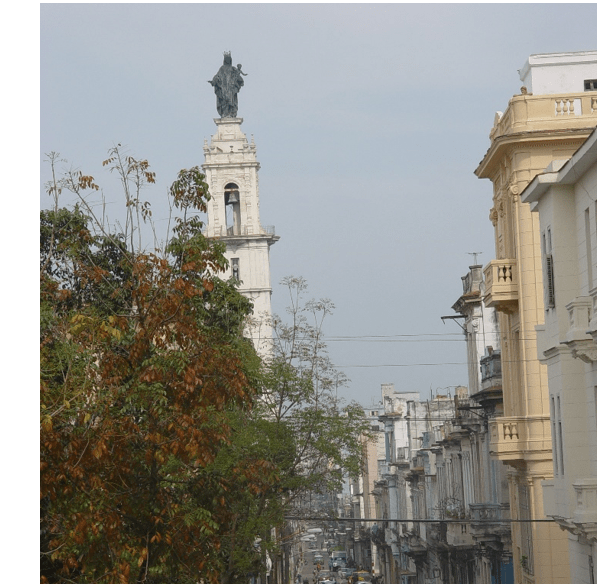

The scene that TM portrays in his journal entry of a memory from the year before he entered Gethsemane, portrays, in a sense, two paths, two visions for life. One “opens toward” the “fake Columbia of the university.” Here TM seems to be referring to the primary building on the campus of the University of Havana, a building designed and patterned after the Library of Columbia University in New York, the school from which he graduated in 1938, from which he received his master’s degree the following year, and in which he was enrolled in a doctoral program at the time of his trip to Havana. Both buildings have a grand set of stairs leading all those who ascend them toward entrances upheld and guarded by massive columns of the ancient Greco-Roman world. Both buildings also share another distinguishing feature in that, mid-way up the staircases of each, is an “Alma Mater” statue – the “Mother” who embodies qualities and virtues such as giving nourishment, fostering, offering blessing, and being benign, gracious, and kind. 2 But it is not toward this window that TM ultimately turns his gaze. Rather, it is toward the other, or more specifically, toward the mirror of the wardrobe that catches the image of the other window, the image of another Kind Mother, Nuestra Senora del Carmen [Our Lady of Mount Carmel]. 3 It is this statue which stands atop the tower of the church of the same name that captures his attention and imagination. There she stands, crowned in humility, presenting her Child whose outstretched infant arms seek to embrace an old City, and beyond, a weary World. It is this Mother whom he will follow, although he can see her at that moment only indirectly – can perceive her only as though through a mirror.

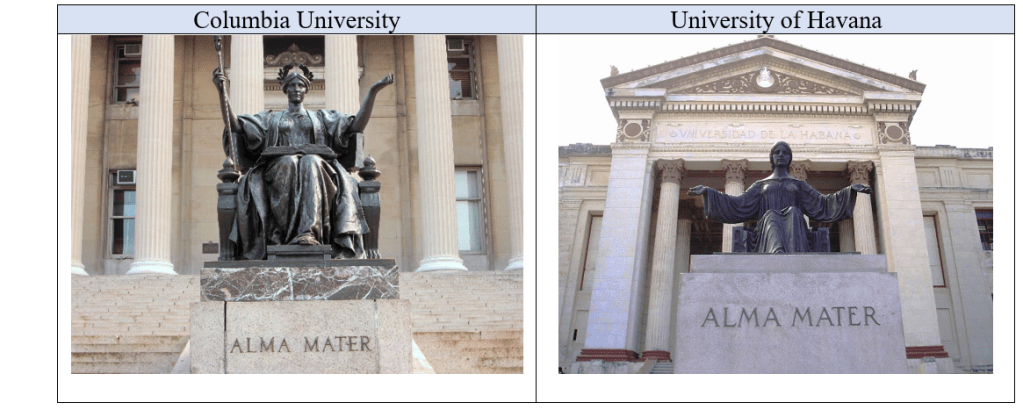

In his journal sixteen years later, TM begins his prayer: “What was it that I said to you, in the mirror, in Havana?” 4 With genuine intimacy, the monk then speaks to the Blessed Mother, “I have never forgotten you. And you are more to me now than then, when I walked through the streets reciting (which I had just learned) the Memorare.” 5 Going on, he confesses that while he cannot remember what requests he had brought to her, what petitions he had made to her, or whether he “received” them, he acknowledges to her that it was … “more important I have received you.” 6 Here, still not addressing the Blessed Mother by any name, TM continues, acknowledging the extent to which she remains somewhat beyond his direct gaze and apprehension: “… more important I have received you. Whom I know and yet do not know. Whom I love but not enough.” 7 This quality of indirection or “hiddenness” is an aura and a presence that TM consistently ascribes to the Blessed Mother over the entirety of his religious life. TM himself offers some context for this in the following passage from his 1961 book, New Seeds of Contemplation, which is only a slightly revised version of the same reflection from his Seeds of Contemplation, published in 1949:

All that has been written about the Virgin Mother of God proves to me that hers is the most hidden of sanctities. What people find to say about her generally tells us more about their own selves than it does about Our Lady. For since God has revealed very little to us about her, men who know nothing of who and what she was only reveal themselves when they try to add something to what God has told us about her. And the things we do know about her only make the true character and quality of her sanctity seem more hidden. We believe that hers was the most perfect sanctity outside the sanctity of Christ, her Son. But the sanctity of the Blessed Virgin is in a way more hidden than the sanctity of God … 8

Endnotes

- Thomas Merton, The Secular Journal of Thomas Merton. New York: Farrar, Straus, & Cudahy, 1959, page 97. Lawrence Cunningham offers the following note on this experience: “On a visit to Havana in 1940, Merton had a profound spiritual experience as he saw the reflection of the church of Our Lady of Mount Carmel in a mirror in his hotel room” (Thomas Merton, A Search for Solitude: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Three 1952-1960. Ed. Lawrence S. Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996, page. 46.) See below an image of the “tower of Nuestra Senora del Carmen” and its “great statute of the Blessed Virgin” in Havana, Cuba. Image retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: File:Habanacocotaxineptunodesdeuh.JPG – Wikimedia Commons

- “almus,” Dictionary of Medieval Latin from British Sources: https://logeion.uchicago.edu/almus. Below are side-by-side images of the Alma Mater statues at Columbia University and the University of Havana. The photo of the Columbia statue was retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: File:2014 Columbia University Alma Mater closeup.jpg – Wikimedia Commons And that of the University of Havana was taken from the Wikipedia article about that university: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/University_of_Havana

- While it may have only been referenced as the identification of directions and location, it is at least interesting to note that TM indicates that the second window, the “other” window, opens … “towards the Calle San Lazaro,” the road of the one whom Jesus “awakens from sleep” (Gospel of John: 11.11). Vulgate: “These things he said; and after that he said to them: Lazarus our friend sleepeth: but I go that I may awake him out of sleep.” Douay Rheims: “haec ait et post hoc dicit eis Lazarus amicus noster dormit sed vado ut a somno exsuscitem eum”

- Thomas Merton, A Search for Solitude: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Three 1952-1960. Ed. Lawrence S. Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996, page. 46.

- Thomas Merton, A Search for Solitude: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Three 1952-1960. Ed. Lawrence S. Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996, page. 46. The Memorare prayer has a significant history and evolution, and for quite a long time, it was mistakenly attributed to Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1153). Offered here is the popular 20th century version of prayer, the version that TM most likely memorized, recited, and prayed. Latin: “MEMORARE, O piissima Virgo Maria, non esse auditum a saeculo, quemquam ad tua currentem praesidia, tua implorantem auxilia, tua petentem suffragia, esse derelictum. Ego tali animatus confidentia, ad te, Virgo Virginum, Mater, curro, ad te venio, coram te gemens peccator assisto. Noli, Mater Verbi, verba mea despicere; sed audi propitia et exaudi. Amen.” English: “REMEMBER, O most gracious Virgin Mary, that never was it known that anyone who fled to thy protection, implored thy help, or sought thy intercession was left unaided. Inspired with this confidence, I fly to thee, O Virgin of virgins, my Mother; to thee do I come; before thee I stand, sinful and sorrowful. O Mother of the Word Incarnate, despise not my petitions, but in thy mercy hear and answer me. Amen.” Both the Latin and the English versions of the prayer were retrieved from Thesaurus Precum Latinorum [Treasury of Latin Prayers]. This site also offers a brief and helpful history of the prayer: http://www.preces-latinae.org/thesaurus/BVM/Memorare.html

- Emphasis mine. Thomas Merton, A Search for Solitude: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Three 1952-1960. Ed. Lawrence S. Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996, page. 46.

- Emphasis mine. Thomas Merton, A Search for Solitude: The Journals of Thomas Merton, Volume Three 1952-1960. Ed. Lawrence S. Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins, 1996, page. 46.

- Emphasis mine. I am grateful to Kenneth M. Voiles for highlighting this passage in his article, “The Mother of All the Living: The Role of the Virgin Mary in the Spirituality of Thomas Merton,” Spiritual Life, 36.4 (Winter 1990), pages 217-228. Directly following this note is a comparison of the two versions with the modest revisions highlighted in blue ink. The 1961 version appears at the beginning of Chapter 23, “The Woman Clothed with the Sun.” See Thomas Merton, New Seeds of Contemplation, New York: New Directions Books, 1961, page 167. The 1949 passage appears toward the end of Chapter 13, “Through the Glass.” See Thomas Merton, Seeds of Contemplation, Norfolk, CT: New Directions Books, 1949, page 100.

Leave a comment