As was indicated in the last reflection, when Henri de Lubac began his study of Buddhism, he was gifted with a copy of the Indian Buddhist text, Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra, which is attributed to Asanga (c. 320-390), by his friend Abbe Jules Monchanin (1895-1957). 1 In his reflective writings, Pere de Lubac describes the occasion on which he received of the Indian Buddhist text, the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra (MSA), from his friend. He praises the work as a “combined masterpiece [chef-d’œuvre] of Mahayana thought and Western Indianism” and affirms it as the “dream” or “perfect stimulant” [le stimulant rêvé] to initiate his Buddhist studies. 2

To provide at least some context for Father de Lubac exuberance for the gift of Abbe Monchanin, we turn to an article written by the esteemed Japanese scholar, Gadjin M. Nagao, who spent much of his life studying the MSA. The essay is entitled, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna- sūtrālaṃkāra.”

Toward the beginning of his essay, Professor Nagao identifies “karuna” as his focus, and states that it appears as the “standard word corresponding to English ‘compassion.’” 3 He also clarifies that karuna [compassion] is “always described in terms of ‘bodhisattva’s compassion,’ which involves the Buddha’s compassion also at the same time.” 4 He then offers a context for “bodhisattva”:

Throughout the MSA, the term ‘bodhisattva’ is used to denote a superior distinguished personality who seeks to obtain Buddhahood but has not yet reached it. Or rather in the opposite direction, it is a human being who has descended from out of Buddhahood, taking birth in this world in the form of human existence for the benefit of other beings. In any case, a bodhisattva is an ideal form of human being; hence it involves the Buddha’s characteristics also. 5

With regard to the depiction of compassion in the MSA, Professor Nagao writes:

Compassion means to ‘to share others’ sufferings, and naturally it is itself characterized by pain and suffering. Observing the sufferings of all sentient beings, when a bodhisattva becomes compassionate toward them he shares the same suffering and himself comes to suffer greatly. 7

Here the Professor references verses 33 and 49 of the MSA, for which he offers the following translations:

Observing that the world is of the nature of suffering, the compassionate one … suffers (by this fact), and he truly knows it, as well as the means to get rid of. Or, further, he does not become exhausted (in his practice of these means). (33) 8

Out of compassion for the sake of living beings they do not forsake the suffering by which the transmigrational life is constituted. What suffering for the benefit of others will the compassionate ones not embrace? (49) 9

In his essay, “Buddhist Charity,” Henri de Lubac would praise those beings who manifest such qualities, “the great Bodhisattvas, often called ‘the Compassionate Ones.” And he offers a quotation from the MSA:

The Bodhisattva … has the love of creatures in his very bones, as one loves an only son. As a dove cherishes its little ones and will not move until it has hatched them out, so the Compassionate One loves the creatures, his children …

The world is not able to bear its own misery. How much less then can it endure the misery of the mass of others. The Bodhisattva is the opposite of this; he is able to bear the misery of the whole mass of living creatures, of all who are in the world. His tenderness toward creatures is the highest miracle in the universe; or rather no miracle at all, since he is identical with others, and creatures are like himself to him … 10

Endnotes

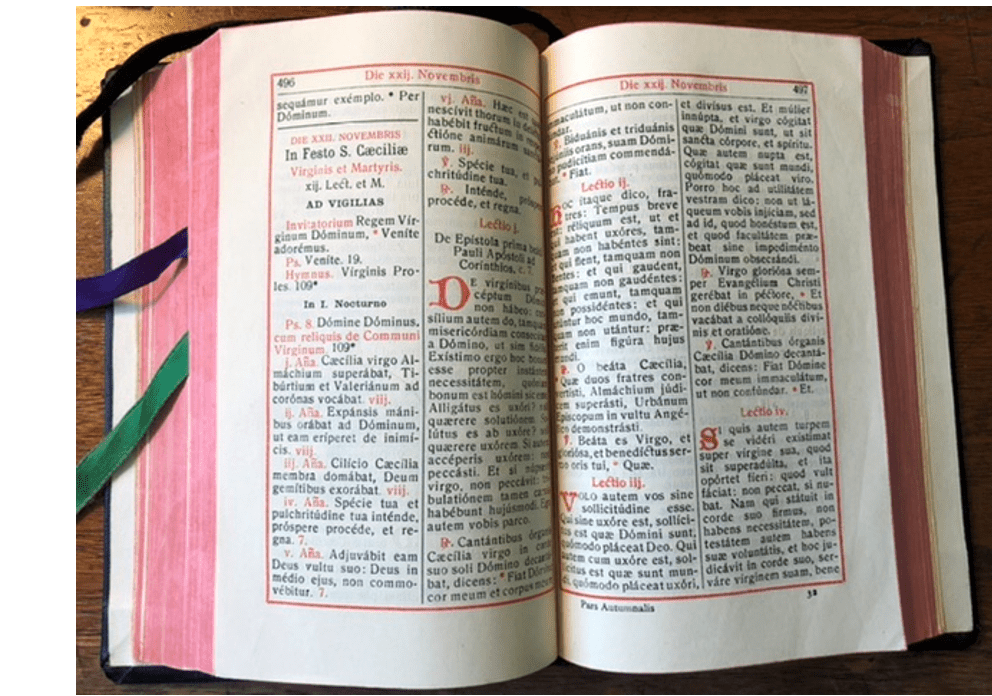

- In a journal entry, dated “November 22, 1968. Darjeeling,” on the Feast of Saint Cecilia the Martyr, TM writes: “In his preface to a book on the Abbe [Jules] Monchanin, a Frenchman who became a hermit on the banks of the sacred river Cauvery in South India, Pierre Emmanuel writes of vocation: ‘What is a vocation? A call and a response. This definition does not say everything: to conceive the call of God as an expressed order to carry out a task certainly is not always false, but it only true after a long interior struggle in which it becomes obvious that no such constraint is apparent. It also happens that the order comes to maturity along with the one who must carry it out and that it becomes in some way this very being, who has now arrived at full maturity. Finally, the process of maturing can be a mysterious way of dying, provided that with death the task begins …. There has to be a dizzying choice, a definite dehiscence (rupture) by which the certitude he has gained of being called is torn asunder. That which – as one says, and the word is rightly used here – consecrates a vocation and raises it to the height of the sacrifice which it becomes is a breaking with the apparent order of being, which its formal full development or its visible efficacy.” (Thomas Merton, The Other Side of the Mountain: The End of the Journey, The Journals of Thomas Merton: Volume Seven 1967-1968. Edited by Patrick Hart, O.C.S.O. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1998, page 296. The Pierre Emmanuel quotation appears in TM’s journal in French, which the editors of his journal kindly translate.) See below a photo of the first pages of the Feast of Saint Cecilia from the Cistercian Breviary. (Breviarum Cisterciense, Pars Autumnalis. Westmalle, Belgium: Typis Cisterciensibus, 1951, pages 496-497).

- Original French: « Au bout de cinq minutes il nous mettait en mains le Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra. Il y avait heureusement une traduction de Sylvain Lévi. Ce chef-d’œuvre conjugué de la pensée mahayanique et de l’indianisme occidental était le stimulant rêvé. » English Translation: “After five minutes he put the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra in our hands. Fortunately, there was a translation by Sylvain Lévi. This combined masterpiece of Mahayanic thought and Western Indianism was the dream stimulus.” (Jérôme Ducor, “Les écrits d’Henri de Lubac sur le bouddhisme”. Les cahiers bouddhiques (in French). Paris: Université Bouddhique Européenne, 2007, 5, page 82.) I am very grateful to DeepL Translate and Google Translate.

- Gadjin Masato Nagao (1907-2005) “served at Kyoto University from 1931-1971” in various positions. Of the Japanese scholar, Jonathan Silk, writes: “It is no exaggeration to suggest that Nagao revolutionized the study of Indian and Tibetan Buddhism in modern Japan.” Another reflection of Professor Silk offers a glimpse of Professor Nagao’s character and his engagement of the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra: “Prof. Nagao was perhaps the most thoughtful and careful person I have ever met … I do not mean that he was shy, for he certainly was not, nor that he was not bold, for he was. Rather, it is that I never knew him to act precipitously, never knew him not to take his time and consider a situation, or a question. I recall well any number of occasions on which a student asked what seemed to me a perfectly simple question, with a quite obvious answer. Prof. Nagao would ponder and consider, before replying. And more than once his response to such questions was that he did not know the answer. It took me a while to realize that it was not that I knew the answer to some question that baffled him, but rather that he could not sufficiently discern the motivation and intent of the questioner, could not perceive what the question really was, and thus was unable to provide an answer that could address what the questioner really needed to know. It is that care and humility which characterized his approach to the works of the Buddhist masters he studied, and why, although he studied the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra for some seventy years, he always felt that there was more to understood, always conscious of the profundity of the text and his own finitude before it …” (Jonathan A. Silk, “Obituary Gadjin Masato Nagao (1907-2005),” The Eastern Buddhist: New Series, Volume 56, Nos. 1&2, 2004, pages 245 and 250 respectively). Writing some years earlier, Professor Silk reflects: “The Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra is a text Prof. Nagao has been studying carefully for more than sixty years …. The text is clearly very much alive for him, in a way that perhaps only more than half a century’s intimacy with it can bring.” (“Preface,” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page viii. Professor Silk’s “A Short Biographical Sketch of Professor Gadjin Masato Nagao” also provides a helpful introduction to Professor Nagao’s significant scholarly engagement of Tibetan Buddhism and the writings of Tsongkhapa.)

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 3.

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 3.

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 3, note 4.

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 7.

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 11. Another alternative translation: “When she observes the natural suffering of the world; the loving (bodhisattva) suffers; yet she knows just what it is as well as the means to avoid it, and so she does not become exhausted.” (Universal Vehicle Discourse Literature (Mahayanasutralamkara) (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences) by Lobsang Jamspal, Robert Thurman and the American Institute of Buddhist Studies translation committee. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, 2004, page 233.) This edition also provides a translation of the commentary on the verse by Vasubandhu, the brother of the author (Asanga): “’She suffers’ means that she feels compassion. ‘She knows what it is’ means that she knows suffering just as it is, and the ‘means to avoid suffering’ means that she knows that by which it is destroyed. Thus, knowing the suffering of the cyclic life just as it is and (also knowing) the means of renouncing it, the bodhisattva does not become exhausted thanks to her distinctive compassion.” (Ibid. 233.)

- Gadjin M. Nagao, “The Bodhisattva’s Compassion Described in the Mahāyāna-sūtrālaṃkāra.” Wisdom, Compassion, and the Search of Understanding: The Buddhist Studies Legacy of Gadjin M. Nagao. Edited by Jonathan A. Silk. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2000, page 20. Again, an alternative translation: “Through mercy, for the sake of beings he does not (even) forsake the life-cycle made of suffering; what suffering will the compassionate bodhisattvas not embrace in order to accomplish the benefit of others.” And Vasubandhu’s brief commentary: “All suffering, in fact, is included in the suffering of the life-cycle. In accepting that he accepts all suffering.” (Universal Vehicle Discourse Literature (Mahayanasutralamkara) (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences) by Lobsang Jamspal, Robert Thurman and the American Institute of Buddhist Studies translation committee. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, 2004, pages 237-238.) In his Asian Journal, TM copies words from the ninth chapter of the MSA that he found quoted in Giuseppe Tucci’s, The Theory and Practice of the Mandala: “He has pity on those who delight in serenity, how much more than upon other people who delight in existence.” (Thomas Merton, The Asian Journal of Thomas Merton. Edited from his original notebooks by Naomi Burton, Brother Patrick Hart & James Laughlin. New York: New Directions Books, 1973, page 60.) An alternative and expanded translation of the verse which TM quotes: “Standing there, a transcendent lord surveys the world as if he stood upon the great king of mountains. As he feels compassion for those who delight in peace, what need to speak of other persons who delight in existence.” And Vasubandhu’s commentary: “Standing there (in suchness, a buddha) gazes out over the world … as if he were standing upon the great king of mountains. Upon gazing he feels compassion even for disciples and hermit buddhas. How much more so toward others?” (Universal Vehicle Discourse Literature (Mahayanasutralamkara) (Treasury of the Buddhist Sciences) by Lobsang Jamspal, Robert Thurman and the American Institute of Buddhist Studies translation committee. New York: American Institute of Buddhist Studies at Columbia University, 2004, page 79.)

- Henri de Lubac, Aspects of Buddhism. Translated by George Lamb. London: Sheed and Ward, 1953, pages 27-28. Father de Lubac indicates that the quotation comes from the 13th chapter of the Mahāyānasūtrālaṃkāra.

Leave a comment