In a divinity school podcast episode once, scholar John Behr offered a story to assist the audience connect with the lofty world of “The Fathers of the Church” – and more specifically, Origen of Alexandria’s ultimate place amongst them. He begins by recounting a conversation he had with his wife years earlier. The discussion began with his wife asking him where he would place the various Fathers on a football (soccer) team. Given the excitement in his voice, the British-born priest and scholar clearly reveled in the assignment possibilities: “Obviously, you’d put someone like Jerome and Epiphanius in attack. You’d put Irenaeus in defense. You’d put Dionysius out there somewhere in left field somewhere.” 1 Then moving from imaginative possibilities to historical metaphor, and with the succinctness of a summarizing sportscaster, Fr. Behr reports, “So Origen was the schoolboy who picked up the ball and ran with it. He [thereby] invented the game, ‘Rugby.’ He got kicked off the team. But everybody played Rugby thereafter.” 2

Having been an English “schoolboy” and having played Rugby himself, TM himself might well have related to and empathized with this imaginative recounting. 3 In a journal entry of June 6, 1961, the Cistercian begins by reflecting on his relationship with a very prominent scholar of Christian monasticism after that individual’s recent visit to Gethsemani. Although beginning with this particular relationship, TM’s reflection broadens – ultimately to include his relationship with the community of Roman Catholic theologians:

We had some talks together. He told me I was a pessimist, too anxious, and too negative. Actually, I also had a feeling of an underlying disharmony between us, a kind of opposition and mistrust (mefiance) under the surface cordiality and agreement. He is certainly one of those, one of the very many, who accept any writing I have done only with great reservations. That I can understand. As a theologian I have always been a pure amateur, and professionals resent an amateur making so much noise. 4

As he continues his entry, the Trappist reflects on his understanding of the scholar’s opinions of some of his specific writings and then, he begins a quite unsparing review of his own work. It all leaves the reader feeling quite sad – and feeling something of the pain of its author. And indeed, it is directly after this attempt as literary self-assessment that TM himself names and describes the ultimate source of his suffering:

What hurts me the most is to have been inexorably trapped by my own folly. Wanting to prove myself a Catholic – and of course not perfectly succeeding. They all admit and commend my good will, but frankly, I am not one of the bunch, am I? 5

While there are aspects of Origen’s life and experience within the Church as a voluminous religious writer with which TM could have identified, there was clearly a sense of some hesitation in his comments about the Alexandrian in his writings. In a journal entry dated, “August 14, 1956. Vigil of the Assumption,” TM writes:

‘The Treatise on Prayer’ is the first thing of Origen’s that I have really liked except perhaps the Homilies on Exodus and Numbers. It is simple and great. He really is a tremendous mind, although he often looks ordinary and stuffy. 6

TM’s early impression of Origen would seem to be supported the scholarship of others as well, as is attested by the portrait painted by the Eastern Orthodox scholar John Anthony McGuckin, who also moves beyond an initial perception to reveal the riches and allure of that complex ancient figure:

Origen’s life and scholarly obsessions made him, in many instances, a fussy and text-obsessed thinker. He was, after all, the Christian Church’s first and greatest biblical scholar. He had his magnifying glass poised over every detail of a word’s semantic freight, and would not let his reader go until the last detail had been logged and noted. Such was not a training that could normally be expected to flower into the great psychic and poetic panoramas that are clearly his soul’s inner vision. But then again, he was far more a librarian-scholiast; he was the Christian church’s first great mystic, describing the divine Word’s quest for the soul through the recesses of time and space, and the soul’s fearful search for its lost Lord, in terms drawn from the Song of Songs, where the bride seeks her lover in the starlit garden. Behind Origen’s scholarly and disciplined exterior, there always beat the heart of a poet. 7

Maybe it was his significant reading in the theology and spirituality of the Eastern Church in the late 1950’s, or the courses he would prepare and teach to those fellow monks on topics such as “mystical theology” in the early 1960’s , or maybe his own experience within the Christian Church as an “international rock star,” but TM’s emphatic sensitivity toward and his affinity to the Alexandrian’s cosmic vision would clearly develop over time. This is evident in a letter TM wrote to Hans Urs von Balthasar in September of 1964. It is an intriguing letter because of the content and the language that precedes the Trappist’s brief laudatory reference to Origen:

I see that the attraction of things like Buddhism today resides in the ‘hidden’ sapiential quality which is absent from our purely ‘scientific’ theology and Scripture study. Underneath all the apparent ambiguities of Buddhism about suffering … there is actually a deep wisdom and admiratio [wonder] at the mystery of truth and love which is attained only when suffering is fully accepted and faced. I think that the reality of Buddhism is missed when this deeply delicate admiratio and wonder is missed at the heart of it … In this I think that what one encounters is what Pope John spoke of: the remnant of ‘primitive revelation.’ And this remnant can be detected really by one note beyond all others, I think precisely its sapiential beauty and wonder, as when Buddha held up a flower and smiled, and his disciple understood the whole thing. And how right you are about Origen and how well you use his inexhaustible mine of riches. I am most grateful. 8

Origen comes up again in a letter to the Swiss theologian from July of the following year, when TM notifies the Swiss theologian: “I am sending you a couple of new poems. I thought of you especially when getting out the one of Origen” 9 The poem to which TM refers, entitled simply, “Origen,” is a viscerally passionate defense and praise of the anathematized early church writer.

TM begins the piece directly, without using the ancient writer’s name. He pulls no punches. Nor does he, in any way, hide his own feelings:

His sin was to speak first

Among mutes. Learning

Was heresy. A great Abbot

Flung his books in the Nile.

Philosophy destroyed him. 10

Here TM acknowledges the horrific fate of being “the first.” Being the first theologian to attempt a systematic presentation of Christian theology – a comprehensive and cohesive view of the cosmos from its beginning to its consummation drawing upon the evolving vocabulary of a neophyte religion that was still under mortal siege – was a nearly incomprehensible burden. Embracing this task, Origen turns to the philosophical and religious discourses the Hellenistic culture in which he was born, raised, and formed as a Christian. Drawing from “Philosophy” – Neoplatonism and Neopythagorianism – to synthesize and communicate the new Christian theological vision within the Graeco-Roman culture in which he lived also won him enemies. The great monastic founder, Pachomius (c.292-348 AD) is said to have thrown one of Origen’s books into the Nile as an expression of contempt for academic learning and intellectual endeavors as a spiritual practice. 11

As the poem unfolds, its 20th century author builds his searing defense of the early Alexandrian Christian thinker before those of lesser capacity who would vehemently denounce him. 12 More specifically, TM focuses on the irony that Origen’s efforts and his amazingly creative thought and teachings would long out-pace his strident detractors – and their worlds, realms, and empires. And TM acknowledges that this enduring influence can be credited to a fourth-century monk named Rufinus who translated many of Origen’s writings from Greek into Latin. Through this act of translation and interpretation, Rufinus made available the “blessed fire of love” for the late antique and medieval Western Christian Church:

Yet when the smoke of fallen cities

Drifted over the Roman sea

From Gaul to Sicily, Rufinus

Awake in his Italian room

Lit this mad lighthouse, beatus

Ignis amoris, for the whole West.

Then TM identifies the true anxiety that he believes to have been at the very heart of the persecution of Origen, the appalled and outraged fear that caused members of his own Christian family over generations to assault him with words of “[h]atred,” words such as “[f]rightful blasphemy” and “detestable opinion.” This dark and reactive disquietude led his opponents to attempt another martyrdom against Origen, a martyrdom of memory, that sought to erase his words, his vision, his hope from the record of the Christian discourse. TM names the offence – the core crime of which his accusers found him guilty – to be a questioning of the possibility of eternal damnation: “Since he had said hell-fire / Would at last go out, / And all the damned repent.“

The thought was horrifying and repugnant to even “gentle” thinkers, that “whores,” “heretics,” and even the “devil and his regiments” would – in the end – “go free.” The possibility seemed to threaten the foundation of things and, indeed, the very fabric of the cosmos. But it was to the place whose everlasting existence he questioned that Origen was sentenced, consigned, and “sent” by “various pontiffs.” But others demurred; holy practitioners of the faith, “saints,” would have “visions of him,” and they would sympathetically reflect that he had “erred out of love.” No matter how much condemnation was piled upon Origen, TM rejoices “the medieval West / Would not renounce him.” Even “all” brutally fierce religious adversaries came “together” in the writings of this Holy Man who poured out his all and his everything for Christ and for the Church:

All antagonists,

Bernards and Abelards together, met in this

One madness for the sweet poison

Of compassion in this man

Who thought he heard all beings

From stars to stones, angels to elements, alive

Crying for the Redeemer with a live grief.

Endnotes

- “Fr. John Behr: Origen and the Early Church, Part, 1,” On Script: Engaging Conversations on Bible and Theology. Specific quotation: 14:41-14:51, and larger context:14:31-15:03. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/CmDW2Y5VWAo).

- “Fr. John Behr: Origen and the Early Church, Part, 1,” On Script: Engaging Conversations on Bible and Theology, 14:49-15:10. Retrieved from: https://youtu.be/CmDW2Y5VWAo).

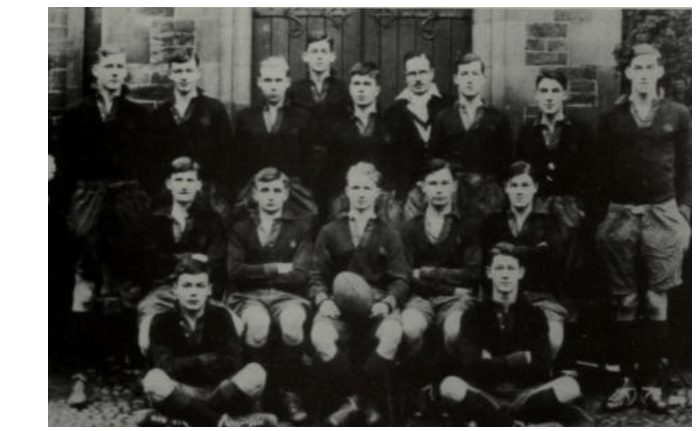

- TM attended the Oakham School in Rutland, England “from the autumn of 1929 to the Christmas of 1932” See David Scott, “An Apophatic Landscape.” Thomas Merton:

Poet, Monk Prophet. Conference Papers from the Second General Meeting of the Thomas Merton Society of Great Britain and Irelandheld at Oakham School, Oakham from March 27-29, 1998, Page 144. Retrieved from: http://thomasmertonsociety.org/Poet/Scott.pdf See photo below of Oakham School Rugby Team with TM, top row, third from left. Retrieved from: Jim Forest, Living with Wisdom: A Life of Thomas Merton. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1991, Page 21. Retrieved from: https://archive.org/details/livingwithwisdom00fore/page/n1/mode/1up - Thomas Merton, The Intimate Merton: His Life from His Journals. Edited by Patrick Hart and Jonathan Montaldo. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999, page 176.

- Thomas Merton, The Intimate Merton: His Life from His Journals. Edited by Patrick Hart and Jonathan Montaldo. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999, page 176-177. I am very grateful scholar Christopher Pramuk for his drawing attention to this particular journal entry of TM: Christopher Pramuk, Sophia: The Hidden Christ of Thomas Merton, Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press, 2009, page 195.

- Thomas Merton, A Search for Silence: Pursuing the Monk’s Life. The Journals of Thomas Merton: Volume Three 1952-1960. Edited by Lawrence Cunningham. San Francisco: HarperCollins Publishers, page 64.

- “Preface,” The Westminster Handbook to Origen. Edited by John Anthony McGuckin. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2004, page ix.

- Thomas Merton, The School of Charity: The Letters of Thomas Merton on Religious Renewal and Spiritual Direction. Selected and edited by Brother Patrick Hart. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1990, page 241.

- Thomas Merton, The School of Charity: The Letters of Thomas Merton on Religious Renewal and Spiritual Direction. Selected and edited by Brother Patrick Hart. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1990, page 288.

- “Origen,” The Collected Poems of Thomas Merton, New York, New Directions Books, pages 640-641. This citation can be used for all subsequent quotations of this poem.

- Pachomius is “generally recognized as the founder of Christian cenobitic monasticism.” Cenobitic monasticism is the form of monasticism which is structured so that monks live together in community. Eremitic monasticism is focused more on monks living as hermits or anchorites. The pioneering figure of the latter form is Antony of the Desert. (Pachomius the Great.” Wikipedia. Retrieved from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pachomius_the_Great) Professor Samuel Rubenson explains: “Pachomius was a holy man, not only by virtue of his ascesis and his visions, but even more by virtue of his discernment, his interpretation of Scripture, and his profound insights.” Acknowledging that the Origen book throwing incident appears in the Greek version of Pachomius’ life, he explains that it is included there within the context of a much larger descriptive scene. And the scholar also affirms that the story is “missing in the Coptic and Arabic versions” of Pachomius’s life. (Samuel Rubenson, “Philosophy and Simplicity: The Problem of Classical Education in Early Christian Biography,” Greek Biography and Panegyric in Late Antiquity. Edited by Tomas Hagg and Philip Rousseau. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000, page 130).

- The stage was set for TM’s engagement with Origen in part by the warm sympathy his religious community, the Cistercians, and one of their own greatest stars, Bernard of Clairvaux (1090-1053), had for the ancient Alexandrian. In the mid-20th Roman Catholic theologians such Hans Urs von Balthasar and Jesuit, Henri de Lubac, truly re-engaged Origen and offered their findings and insights to the larger Church. And re-engagement continues with contemporary scholars such as David Bentley Hart writing powerfully of “Saint Origen”: “But, really, it is the most shameful episode in the history of Christian doctrine. For one thing, to have declared any man a heretic three centuries after dying in the peace of the Church, in respect of doctrinal determinations not reached during his life, was a gross violation of all legitimate canonical order; but in Origen’s case it was especially loathsome. After Paul, there is no single Christian figure to whom the whole tradition is more indebted. It was Origen who taught the Church how to read Scripture as a living mirror of Christ, who evolved the principles of later trinitarian theology and Christology, who majestically set the standard for Christian apologetics, who produced the first and richest expositions of contemplative spirituality, and who—simply said—laid the foundation of the whole edifice of developed Christian thought. Moreover, he was not only a man of extraordinary personal holiness, piety, and charity, but a martyr as well: Brutally tortured during the Decian persecution at the age of sixty-six, he never recovered, but slowly withered away over a period of three years. He was, in short, among the greatest of the Church Fathers and the most illustrious of the saints, and yet, disgracefully, official church tradition—East and West—commemorates him as neither” (David Bentley Hart, “Saint Origen,” October 2015, First Things, Retrieved from: https://www.firstthings.com/article/2015/10/saint-origen)

Leave a comment