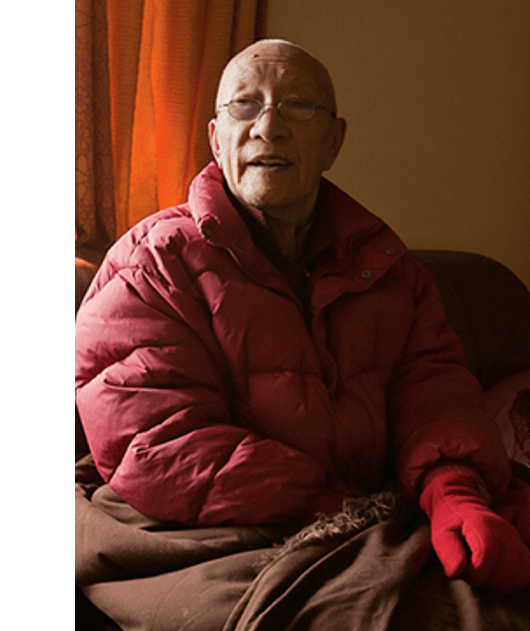

One of the center points of the book known by many in the West as The Tibetan Book of the Dead [Bardo Thodol] is a section called, “The Great Liberation by Hearing.” It is this section that is read to the dying and the dead. An advisor to the Dalai Lama and Dzogchen teacher, Khamtrul Rinpoche 1928-2019, offered an oral teaching on this section that was later transcribed and edited. 1 In the opening portion of this teaching, Rinpoche addresses the role, the presence, and the inner disposition of the attending lama, first offering this general orientation:

Traditionally, the procedures followed when a lama visits a dying or decreased person are intricate and prolonged and will vary depending on whether the person is about to die, has just recently died, or has been dead for some days. 2

Resonating with Julian’s own text, Rinpoche then explains: “When a person is approaching death, it is customary for the relatives and close friends to seek the assistance of a fully qualified lama.” 3 He then begins to describe the energizing aspiration and the level of empathic understanding needed to enact the specified rituals: “The lama should be motivated by a sincere compassion for all sentient beings and should have mastered in his own mental continuum the direct experiential cultivation of the dying processes.” A deep level of inner focus is needed if the lama is to truly respond to the needs of the dying person and to provide a grounding comfort and reassurance to all present:

It is very important that when coming into the household, the attending lama is concentrated on the motivation to free the dying person from the sufferings of cycle existence. Very often the mere presence of an accomplished lama can create a solid sense of calm and purposefulness, which inspires both the dying person and family.

The “formal practice” begins with the lama “taking refuge in the Buddha, the sacred teachings, and the ideal spiritual community.” These objects of refuge are called “The Three Jewels” or the “Three Precious Jewels,” and they reference the Buddha, “the fully enlightened teacher;” the dharma, the teachings, the practices, and the path which lead to transformative liberation; and the sangha, the “companionship” of the practicing community. 4 The concept of “taking refuge” is of foundational importance in Buddhist practice. It might be considered both a practice of initiation – of beginning and commitment – and a practice of continual affirmation and renewal. Taking refuge can also be seen as a practice of motivation:

The successful taking of refuge in the Three Precious Jewels requires the following two conditions: a) a genuine anxiety in the face of the potential for future suffering and b) a genuine confidence in the capacity of the Three Precious Jewels to offer protection from these potential sufferings. 5

And Khamtrul Rinpoche explains that the “formal practice” begins with the lama taking refuge in the Three Jewels “on behalf of the dying person and all sentient beings, including himself.” This process, which appears to have a significant vicarious element as indicated in the words “on behalf of,” extends that element through meditative visualization:

At this point, the lama should visualize in the space in front of him images of the three objects of refuge, the Buddha, sacred teachings, and ideal community – forming a tree, whose branches like billowing clouds in the sky are adorned by buddhas, bodhisattvas and the spiritual masters of the lineage. Then he should visualize that the dying person, surrounded by all sentient beings, takes refuge … 6

Endnotes

- “Acknowledgement.” The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. Translated by Gyurme Dorje. Edited by Graham Coleman with Thupten Jinpa. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006, page x. See image of Khamtrul Rinpoche below retrieved from Rangjung Yeshe Wiki – Dharma Dictionary. This web resource reports that “[f]rom a young age, Rinpoche had visions of the Buddha … Lama Tsongkhapa and others.” Website address: Garje Khamtrul Jamyang Dondrub – Rangjung Yeshe Wiki – Dharma Dictionary (tsadra.org)

- “Context” for Chapter 11, “The Greater Liberation by Hearing.” The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. Translated by Gyurme Dorje. Edited by Graham Coleman with Thupten Jinpa. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006, page 219. Unless otherwise indicated, all quotations in this reflection will be from pages 219-220 of this text.

- “And they that were with me sente for the person to be my curate to be atte mine endinge.” Julian of Norwich, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Eds, Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, Section 2, lines 19-20, page 65.

- “Glossary” The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. Translated by Gyurme Dorje. Edited by Graham Coleman with Thupten Jinpa. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006, pages 504-505.

- “Glossary” The Tibetan Book of the Dead: First Complete Translation. Translated by Gyurme Dorje. Edited by Graham Coleman with Thupten Jinpa. New York: Viking Penguin, 2006, pages 502-503.

- The first and third definitions of “vicarious” in Merriam-Webster Dictionary: “experienced or realized through imaginative or sympathetic participation in the experience of another” and “performed or suffered by one person as a substitute for another or to the benefit or advantage of another.” (“vicarious,” Merriam-Webster Dictionary: Vicarious Definition & Meaning – Merriam-Webster )

Leave a comment