My curate was sent for to be at my ending, and by then he cam I had set up my eyen and might not speake. He set the cross before my face, and said: ‘I have brought thee the image of thy saviour. Looke thereupon and comfort thee therwith.’ 1

In her Short Text, Julian specifies that it is those who are there with her who call for her priest to be present: “And they that were with me sente for the person to be my curate to be atte mine endinge.” 2 Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins very helpfully point out that earlier in the same section of the Short Text, Julian she had already received her last rites:

And when I was thrittye wintere alde and a halfe, God sente me a bodelye syeknes in whilke I laye three days and nights, and the ferthe night I took alle me rightings of haly kykre … 3

This timeframe helps to create a deeper sense of the moment in which the crucifix is placed before Julian, and by whom:

In Middle English, a ‘person’ is usually a parish priest, while ‘curette’ refers to anyone in religious orders responsible for the ‘cure’ of souls. Although Julian has already taken her ‘rightinges of haly kyrke’ earlier, when it was first supposed she was dying, her parson returns to fulfill his responsibility to ease her passing from the world. 4

A Middle English translation of a text attributed to Anselm of Canterbury, Admonitio Morienti, counsels:

Whan a sek man schal ben ennoyted [anointed], þe crucifix schulde ben brouth & he schulde enhowren it in þe worschepe of Ihesu Crist, þat boughte hym with manye harde peynes & schedende of his precious blode, & for þe & me deide vppon þe cros. Amen. 5

And the late Latin text, Ordo ad visitandum infirmum, offers similar pastoral guidance:

And it must be known when a sick person is to be anointed, an image of the Crucified cross [imago crucifixi ] must be offered to him and placed before his sight: that he may adore his Redeemer in the image of the Crucified [in imagine crucifixi], and remember his suffering endured for the salvation of sinners. 6

Scholar Eamon Duffy provides further context to religious environment in which these last rites and rituals were practiced:

Horror and fear are the emotions most commonly associated with late medieval perceptions of death and the life everlasting, and preachers, dramatists and moralists did not hesitate to employ terror – of death, of judgement, and of the pains of Hell or Purgatory to stir their audiences to penitence and good works. But the priest at bedside or graveside had different priorities and the texts of the services for the visitation of the sick and for burial were directed towards reassurance and support …. On the all-sufficiency of the merits of Christ for the sinner … 7

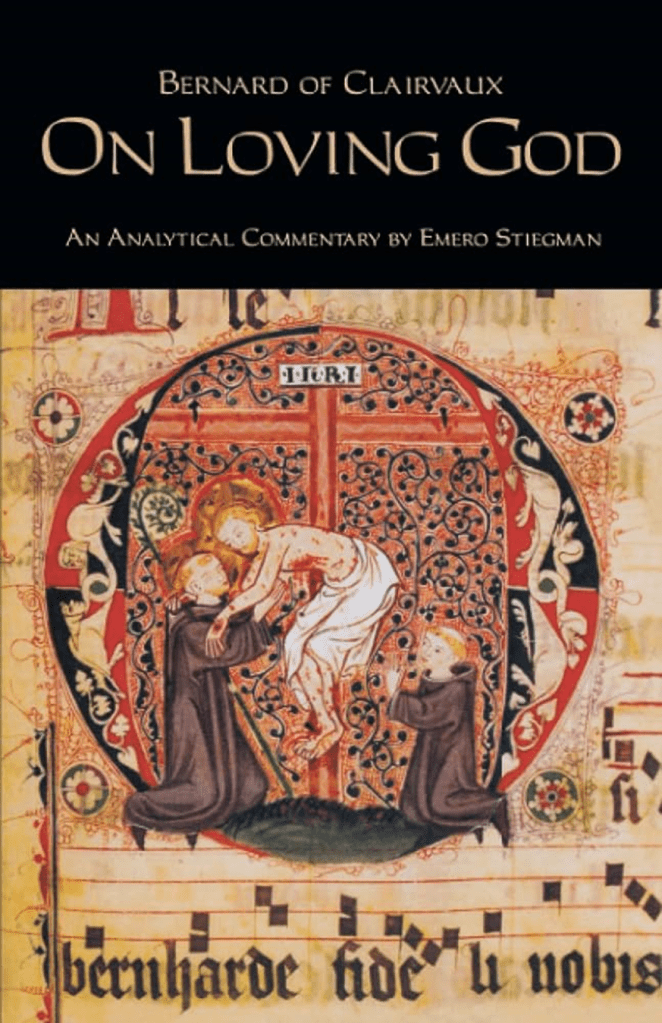

In addition, it was believed that the Devil used the weakened and incapacitated state of the sick to torment them, to tempt them to believe that they were beyond the reach of divine forgiveness, and to drive them to despair. 7 Professor Duffy explains that one of the resources recommended in pastoral manuals to encourage and comfort persons who were facing such spiritual agony was a devotional image associated with Bernard of Clairvaux of the Crucified Christ, who “hung with arms extended to embrace, with head bowed to kiss the sinner, his pierced side exposing his heart of boundless love.” 8 The professor then quotes a medieval manual which provides language for priests to speak to the sick and dying:

Put alle thi trust in his passion and in his deth, and thenke onli theron, and non other thing. With his deth medil [occupy or absorb] the and wrappe the therinne … and have the crosse to fore the, and sai thus; – I wot wel thou are nought my God, but thou art imagened aftir him, and makest me have more mind of him after whom thou art imagened. 9

Endnotes

- Julian of Norwich, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Eds, Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, Chapter 3, lines 17-20, page 131. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins note: “The dying were supposed to gaze at the cross during their final agony … A crucifix was typically typically an effigy, perhaps painted, of Christ on the cross, arms outspread, head slightly bowed to one side, body twisted, with one ankle laid over the other and a single nail transfixing both.” (Ibid. 130).

- Julian of Norwich, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Eds, Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, Section 2, lines 19-20, page 65.

- Julian of Norwich, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Eds, Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, Chapter 3, lines 1-3, page 131, with editors note on page 130.

- Editors’ note from Julian of Norwich, The Writings of Julian of Norwich, Eds, Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. University Park, The Pennsylvania State University Press, page 64.

- “St. Anselmi Admonitio morienti,” Yorkshire Writers: Richard Rolle of Hampole and His Followers. Edited by C. Horstmann. D.S Brewer, 1985/1999, Volume 1, page 107. I am very grateful to Professor Amy Appleford for highlighting this quotation in her rich and helpful article: “The ‘Comene Course of Prayers’: Julian of Norwich and Late Medieval Death Culture.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 107, no. 2, 2008, 190–214, and page 198 in particular.

- Latin text: “Et sciendum est quando infirmus debet inungi, offerenda est ei imago crucifixi et ante conspectum ejus statuenda: ut redemptorem suum in imagine crucifixi adoret, et passionis ejus quam pro peccatorum salute sustinuit recordetur.” Quoted in: Amy Appleford, “The ‘Comene Course of Prayers’: Julian of Norwich and Late Medieval Death Culture.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 107, no. 2, 2008, page 198. English translation from Google Translate.

- See Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992, page 314.

- Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992, page 315. See image below which is identified on the book’s back cover as a “[miniature] from a Gradual from the Cistercian nuns’ house in Wonnental in Breisgau.”

- See Eamon Duffy, The Stripping of the Altars: Traditional Religion in England 1400-1580. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992, page 315. See a slightly different version of this guidance quoted in Amy Appleford, “The ‘Comene Course of Prayers’: Julian of Norwich and Late Medieval Death Culture.” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 107, no. 2, 2008, pages 198-199.

Leave a comment